The Silence and Eloquence of Objects: a ‘one-room’ hung on the ceiling of Istanbul Modern

by Nora Tataryan

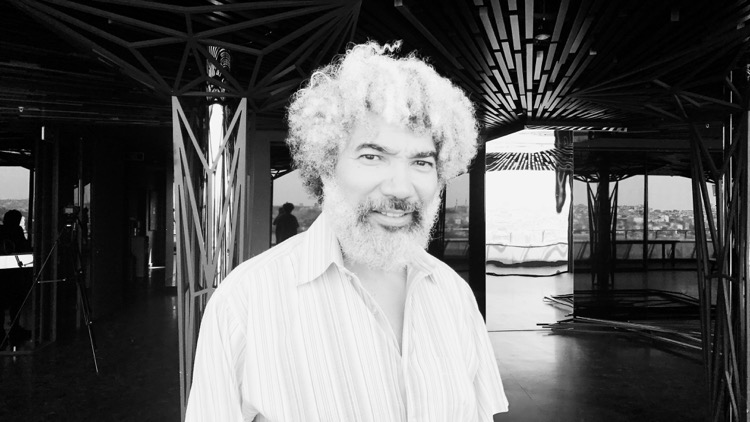

For the 15th Istanbul Biennial, Young-Jun Tak hung a replica of his former one-room Seoul apartment upside-down on the ceiling of Istanbul Modern and created the piece called The Silence and Eloquence of Objects. Most of the furniture which used to occupy the artist’s one-room in South Korea was specially brought from Seoul and installed on the ceiling of the museum after having been painted white. With this work, Young-Jun Tak, who critiques political and social events through personal experiences, hints at the global economic crisis which he was born into and the fluidity of the concept ‘home’. We talked with Young-Jun Tak about his work and general art practice.

Could you describe how you got involved with the Biennial and how your project has been evolved?

I took part in a group exhibition, The Others, at König Galerie in Berlin, which was also curated by Elmgreen & Dragset. Afterwards, I received an invitation to the Biennial from them again.

I have never really liked places where I lived in South Korea. Particularly, the scrappy small ones that I’ve rented for myself in its capital city, Seoul, were nothing but private warehouses for clothes and books, five-minute breakfast stations and sleeping spaces. But, somehow, thanks to the poor housing conditions, I might have been able to reach out to their outer surroundings more often, and those experiences such as visiting art exhibitions and openings have structured the current me. As I recently relocated my whole life in Berlin, I decided to convert one of them into an artwork as a homage to dislike of my previous apartments in Seoul.

The Silence and Eloquence of Objects is an installation inspired by your flat in South Korea and it explores domesticity, being confined in a private space, mobility etc. Could you describe your work, the feeling behind it and the ways in which it speaks with the title of the Biennial, a good neighbour?

This new project is a full representation of the 24 square meters of my second flat in Seoul. Most of the furniture and items in the piece are mine. The work’s size and objects’ arrangement are also measured up to the actual flat. Few exceptions are belongings to the flat, so, in order to substitute them, I found the most similar furniture to ones that I used. It might be quite big as an artwork, but perhaps not so grand as a living place. In Seoul, where living-cost and rent fee are rocketing high in comparison to low income, lots of young people live in such a tiny room-like apartment, called “one-room”. There’s no division between a bedroom, kitchen, living room, and sometimes landlords even separate one big room into two small ones by installing an awkward wall. If you’re unlucky, your landlords might increase the rent fee every single contract year according to the city’s non-stoping gentrification. I didn’t have any pleasant feeling to my places and simply didn’t care about interior design or cosy ambience. As a result, my area started being complied with cheap, easy-to-carry furnishings. Not only in Seoul, but also in many crowded cities in the world, people – especially young generation – would live up with such housing issues. My generation welcomed our 20’s with global economic crisis and was overwhelmed by depression and frustration upon the shadowy present and future. And, now, never-ending political turbulences in many places in the world are damaging lots of precious values that we’ve agreed upon and preserved. My youth has been very grateful just to stability, not even to progress. Of course, for us, home ownership is an unreachable life goal unlike former generations.

Perhaps, that’s why the whole one-room is hung from the ceiling upside down like as our reality and given circumstances. My life is not grounded in it anymore. Even when I lived in the very space for two years, I denied to identify any aspect of it with myself and rather thought about what comes next. For some people, the notion of ‘home’ can be still something settled and stable, but what I’ve experienced so far regarding that concept is more close to fluidity. Also, as a young gay man who lived in a sexually conservative society, I have preferred this kind of metropolis-oriented urban life to involve myself in bigger gay communities, and flexibility and adaptation have become priority in my ways of living.

In my work, all object surfaces are structured with white acrylic paste and then painted in white acrylic. While I was painting the entire surface in white in this white cube of Istanbul Modern, it was like erasing the whole form. However, as you can see the painterly structured surface all over the work, I gave it very expressive skin, and its existence is created and emphasised by every single brush stroke. It corresponds to how home affects your identities. No matter if you hate your unattractive place or not, and if you try to eliminate any evidence of your personality and character from the ugly home or not, your being there in your place in/directly marks on you, and vice versa. And, of course, covering a young single man’s apartment with creamy paste and liquid paint in white evokes a certain sexual connotation. Also, white is an easy colour for audience to picture their own memories, thoughts, feelings and imaginations about home and living upon the work. Like a blank white canvas or MS Word page on your computer screen.

Ironically, the place that I always looked down on became something that everyone looks up now. It’s also a bit weird that some people comment on it as a ‘beautiful’ artwork just because the place is only simply covered with white paste and paint, although my living style and housing condition in the squeezed space were trivial and shabby. I wasn’t willing to invite anybody in the place, but finally now I can say ‘welcome to my home!’

How this specific installation speaks with your art practice in general?

My works combine contrasts and bring conflicts in. They can be about historical, art historical, political, ideological, religious, or social issues. For instance, Salvation (2016) is a life-sized praying Madonna sculpture and it is collaged with black and white flyers, which were printed and distributed by conservative Korean Protestant groups to oppose and hinder the development of LGBT rights. In The Silence and Eloquence of Objects, I played with art historical sides more. From a distance, you might be able to see minimalistic forms in my work. But, the more you come close to it, the more you would discover impressionistic painterly aspects. Also, again, from far away, you would read it as an abstract sculpture through its squares and grids, but in close-up you can realise that it consists of variety of readymades in everyday life. Furthermore, I wouldn’t mind if you define it as an installation, sculpture or even painting.

In terms of art making, I enjoy time-consuming, patient, receptive processes like collages, overlapping paint layers, and hand rubbing clays. In this new project for the Biennial, the continual strong brush strokes are very noticeable. These sorts of working methods are actually not so welcomed in our speedy society. I wouldn’t have allowed to indulge myself with doing such stuff, particularly, when I lived in the apartment in Seoul. Also, I don’t aim to duplicate things as a result of the repeated activities. Every single line, curve, bump and lump on the paste layer are all different. In the end, it depends on how you perceive them.

What do you think of Istanbul? What does it mean to you to exhibit your work in this city in this specific time period?

The notion of ‘neighbour’ can exist because of me and you, and where you’re located. We can start to think of neighbours or a good neighbour from looking at where and how I live(d). Even though my work is a replica of a very specific place belonged to me, I hope viewers expand their thoughts on the Biennial’s theme by bringing their own stories about housing issues through the piece.

This is my second time in Istanbul. Istanbul has been my dream city since my childhood. Strolling around Hagia Sophia, Blue Mosque and Topkapı Palace and exploring newly gentrified Karaköy and Asian side of the city fascinate me. But, this time, I feel more like ‘living’ here than just visiting. And then, naturally, if your imaginary dream becomes daily reality, it can be quite harsh and tough sometimes.