Exhibited works

In The Summer Of 1989 Mr. McManus Cut Down A Rosebush That Was Growing Directly On The Border Between The McManus’s Back Yard And The Black’s Back Yard. The Resulting Donnybrook Was The Most Brutal Things Us Kids Had Ever Seen In Real Life. Years Later I Figured Out The Fight Wasn’t Really About Roses., 2013

Acrylic and pencil on board

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Aaron Zulpo

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

On Tuesday, July 1, 1980, In Billings, Montana, Which Is In The Southern Quadrant Of The State, It Was 70 Degrees Which Is Hot Enough To Make Most People Stay Inside In The Afternoon Except Maybe Kids, And Being Close To The Fourth Of July The Kids Would Have Been Lighting Fireworks And Watching Them Pop And Sizzle Into The Big Blue Sky Over The Peaks Of The Bighorn Mountains Like Man-Made Comets Or Magic Spells. Just South Of Town The Heat Would Have Left Two Kids Looking For A Shady Place To Kiss, Which Would Lead Them To Pictograph Cave, A Sacred Site Excavated By Archaeologists In The 1930’s Where 106 Pictographs Were Found, Some As Old As 2000 Years, Whose Origins Still Leave Everyone Guessing Because Generations Of Native Americans Have Added Onto The Existing Pictures Again And Again So That The Stories Of Old Battles Intersect With The New, Confusing History, And Maybe It Was These Things A Slight Girl With Green Eyes And Straw-Colored Hair Who Liked To Draw And Who Was Between Her Eighth And Ninth Grade Year, Was Thinking Of While She Studied A Horse-Shaped Pictograph Under A Boy Who Was A Bit Older, With Brown Hair And Eyes And Who Liked Cars, Who Burst Inside The Girl, Unleashing Bits Of Things And Other Things That Would Become Me, Already Unwanted. Or Maybe The Girl Was Thinking Of The Little Bighorn Monument Where They Had Guzzled Wine Coolers Earlier While Treading The Same Ground Where General George Armstrong Custer Breathed His Last Wicked Breath At The Hands Of Brave Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, And Arapaho Warriors Whose Ghosts The Girl Thought She Could Sense Snaking Through The Bear Grass And Old Graves, And Maybe It Is Because Of These Things That Even Now, 36 Years Later, I Love Horses And Justness And Fireworks And Stories., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Jennifer Ley & Kit Skarstrom

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

Bored Girls In Painting Class., 2016

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Antonio Colombo Arte Contemporanea

On Tuesday, March 24, 1981, In Billings, Montana, Which Is Nicknamed The Magic City For Its Rapid Growth As A Young Railroad Town In 1882, News Reports Said That An Earthquake Had Hit New Zealand Which Was Hardly Any Consequence At All In The Western United States Except For Maybe The Slightest Tremor Felt Under The Feet, More Of A Shiver Than A Shake, Imperceptible To Most Humans But Noticed By The Sensitive Beasts Of The Nearby Pryor Mountains Mustang Herd, A Group Of Wild Horses Deemed, Because Of Their Unique Genetic Makeup, The Most Significant Wild Horse Herd Remaining In The United States. This Day, In A Courtroom Downtown, A Judge Was Deciding A Very Large Case In Which The Crow Tribe Of Montana Sought To Ban Hunting And Fishing Within Its Reservation By Anyone Who Was Not A Member Of The Tribe, Citing Its Purported Ownership Of The Bed Of The Bighorn River, On Treaties Which Created Its Reservation, And On Its Inherent Power As A Sovereign, But The Judge Was Currently Ruling, With Coffee On His Breath, That This Was Not To Be, And That Hunting And Fishing Areas Of The Crow Reservation Would Continue To Be Open To Anyone, Stating The Treaties Of 1851 And 1868 Did Not Convey Ownership Of The Riverbed To The Crow Tribe, And He Said This In A Voice As Hollow As The Halls In Which They Sat, The Judge And Members Of The Crow Tribe. It Was Noon, And Across Town A Slight Girl With Green Eyes And Straw-Colored Hair Writhed In Pain As A Baby Girl Struggled Out Of Her, Me, And She Knew What I Didn’t Know Yet Because How Could I, That Even As The Doctor Readied The Blade To Slice The Umbilical Cord, That A Man Outside Check His Watch And Waited To Transport Me Somewhere Else, I Don’t Know Where, To Be Adopted To Someone Else. To Move On From This I Will Now Talk About The Moon That Night And How It Was A Waning Gibbous Moon, Meaning 85 Percent Of It Was Illuminated, The Moon Of Demeter, Which Traditionally Marks A Harvest Sacrifice To The Earth Mother, A Moon In Which Its Followers Are Advised To Disconnect From Unwanted Situations, Banish What Shouldn’t Be There, And Remove Obstacles. A Sad Day On Many Fronts., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Michael Zamsky

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

My Sister’s Bush Was Glorious And Full And The Color Of Campfire Flames While Mine, Still Struggling Through Puberty, Was Patchy And Mousy And In Her Presence I Felt Like An Unfinished Drawing., 2016

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Hometown Gallery

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

The Johnson Boys Used To Set Off Fireworks In Their Mother’s Home, Which Was Too Nice For Them, While We, Who Were Too Nice For The Johnson Boys, Pined Over Them Fiercely From Afar. They Didn’t Know We Existed., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

Collection Nina Hale

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

The Bad Boys Hung Around The Baseball Diamond Being Dangerous And Irresistible., 2014

Acrylic and pencil on wood

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Harvey Fierstein

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

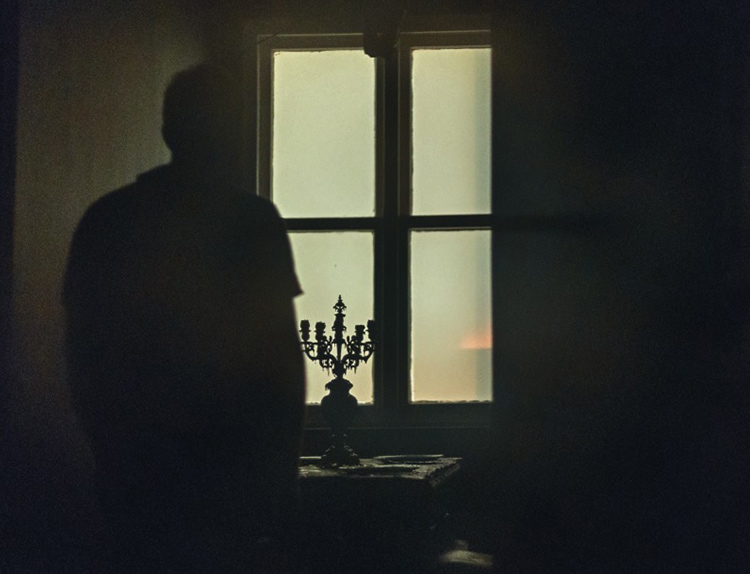

Mr. Leland Had Served In The Military For A Time And When He Came Back My Parents Said He Was A Little Off. Everything Had To Be Perfect, From The Way The Lawn Was Cut To How Mrs. Leland Shaved Her Legs. He Almost Always Chewed Cinnamon Gum And We Were Terrified Of Him., 2012–14

Acrylic and pencil on wood

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Lindsay Gallery (Columbus, OH)

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

In Our House And Others I Knew, Redecorating Was A Way To Force Change Without Really Changing Anything At All., 2014

Acyrlic and pencil on wood

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Mara Baldwin and Sara Hennes

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

It Must Have Been Around 1992 When A Rare Bird Built Its Nest In The Park Across The Street From My Parent’s House And The Hunter A Few Houses Down Wanted To Slay It And The Boys Named Chris And Colin, Whom I Disliked, Wanted To Steal Its Eggs To Hatch Under Their Pillows, And The Beautiful Girl Named Mandy Wanted To Pluck Its Feathers For Her Hair, And I Wanted To Be It, The Bird, Impermanent And Candy-Colored And Wanted By All., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

The Failed Panty Raid of 1993., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Nina Hale

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

I Envy Those Who Are Not Afraid To Be Alone, And Who Are Not Afraid Of The Dark Or Of The Moon Spilling Over Them Or Of Robbers Or Ghosts Or Silence., 2017

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Jennifer Ley & Kit Skarstrom

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

At The Very Same Time Each Evening The Family Down The Road Prays Before They Eat Dinner In Front Of A Big Picture Window And When I Am Feeling Especially Small I Am Jealous Of Their Certainty And Of The Sturdy Wooden Chairs Holding Each Of Them In Place., 2016

Acrylic and pencil on panel

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Emma Allen & Alex Allenchey

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).

If You’re Okay Then I’m Okay And We Can Do This Until We’re Very Old., 2012–14

Acrylic and pencil on wood

Courtesy of the artist

Collection Lisa Waltuch & Jon Zeitlin

Presented with the support of Nicelle Beauchene Gallery (New York).